When one hears the word “Viking,” it almost instantly conjures images of brawny warriors wielding fierce swords, riding in waves of long ships to pillage and plunder unsuspecting villages. It’s an accurate image, though not a complete one.

The Vikings, more than almost any other people that actually lived in history, have taken on a mythological reputation. This is likely because we simply know so little about the Norsemen — literally, “men of the North.” Most of the writings from their time period were written by Christians, who were one of the main targets of Norsemen raids. As the monks and other historians weren’t keen on fondly remembering the Vikings, they didn’t give them much space in their records.

Consequently, few detailed accounts exist of this Northern Germanic people. What we do know is for the centuries roughly spanning 700-1100 AD, the Norse emigrated all over Europe, literally and figuratively spreading their seed throughout Ireland, England, France, Germany, and even Greenland and Canada’s Eastern shores; if you have Northern European ancestors, there’s a good chance you have some Viking in you. As to our knowledge of Viking culture, we are largely limited to reports of their martial endeavors, conveyed in vague descriptions like “the Northmen at this time fell on Frisia with their usual surprise attack,” and, “the Northmen got to Clermont where they slew Stephen, son of Hugh, and a few of his men, and then returned unpunished to their ships.” As author Anders Winroth notes in The Age of the Vikings, our only surviving descriptions are “the Vikings show up, ravage, and kill many if not all.”

This dearth of historical information has turned the Norsemen into a pure symbol of the warrior archetype, and raised their standing to that of near gods. They didn’t see themselves in that regard, however. The Vikings had their own pantheon of revered deities, as well as accompanying stories of the role these gods and goddesses played in creating the world, spurring mortals’ heroic deeds, wreaking destruction, and catalyzing renewal.

While figures like Thor, Loki, and Odin are making an appearance in pop culture (and will only continue to do so based on Marvel’s tendency to make sequel after sequel) the old myths behind those figures are even more interesting than the films they star in. On the big screen, all we see are Thor’s heroic deeds of strength, likening him to a Norse version of Hercules. And of other Norse figures, we get almost no information at all.

To the Viking people, these gods provided the very breath of life; they served as models for manhood to Norse warriors. No matter the religion you practice (or none at all), all men can learn from the Norsemen’s myths, just as we can learn from those of Rome and Greece (Got Thumos?). Over the course of a few monthly articles, we’ll explore the Viking worldview and gods, which were different and more complex than their classical counterparts. In some ways, this makes the Norse gods more relatable to us mortals than the likes of Zeus or Hercules (even though he was partially mortal himself).

Today, we’re going to look specifically at Odin. He’s the chief god in Norse mythology — the Allfather. I found his story and the myths surrounding him to be utterly captivating, and he provides an excellent study for today’s man.

Odin’s Origins

Among the many Viking deities who inhabit Asgard, the fortress of the gods, Odin plays the role of Chieftain. But he is not the Creator, nor the first god to come into existence. To understand Odin’s place amongst the Viking deities, we first need to briefly look at the Norse creation story.

Before humanity existed and even before sky or ground or wind, there existed a gaping abyss known as Ginnungagap. At one end of the gap flamed elemental fire and at the other end blew elemental ice. The cold and the heat met in the gap, and the drops formed a frost ogre named Ymir. As frost continued to melt in the gap, a cow emerged named Audhumbla. She fed Ymir with her milk, and she was in turn nourished by salt licks that formed in the ice. As Audhumbla licked away, she uncovered Buri, the first of the Norse gods. Buri had a son named Bor, who with the giantess Bestla had three sons: Odin, along with his brothers Vili and Ve. The three brothers killed Ymir and constructed the world with his corpse. The frost ogre’s blood became the seas and lakes, his flesh the earth, and his bones the mountains.

After assembling the world, Bor’s three sons also created the first humans, Ask (the man) and Embla (the woman). Odin had the most important task, imbuing the first people with spirit and life, while Vili and Ve gave the power of movement and the capability of understanding, as well as clothing and names. Because of Odin’s role in creating the Norse universe, he became known as the Giver of Life.

While this origin myth lives on, it’s possible that the deity is based on an actual man. Snorri Sturluson, a 13th century Icelandic historian, believes Odin was a famous warrior who led his people out of Troy and into Scandinavia. His greatness was such that he ascended to the status of a god, and became worshiped as one. His myth continued to grow, especially among Germanic peoples, and he eventually usurped Tyr as the chief god, both in myth and in religious practice and worship. If this is true or not, we’ll never know, but either way his mythological status has been cemented.

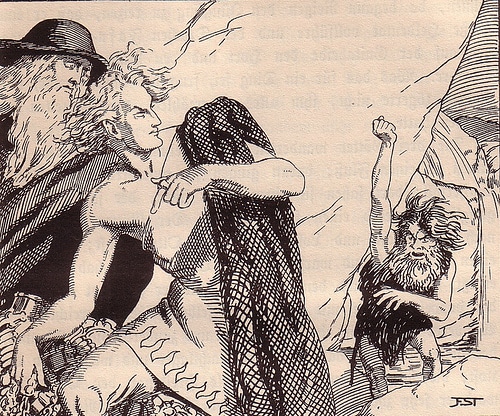

However Odin’s apotheosis came about, he is typically depicted as a white-haired, bearded old man, and often resembles Zeus or the Christian God in artistic renderings. The noticeable difference? Odin has but one eye (we’ll get to that story in detail later), and is most often flanked by an assortment of creatures, namely his ravens and his eight-legged horse.

Odin’s other main companion is his wife, a goddess named Frigg. We don’t have too many important myths about her, but because of her matronage, Frigg was given a day of the week, which to this day is known as Friday. Odin sired many children, the most important of whom for our purposes are Thor and Baldur (we’ll discuss them later in this Norse series). Eventually, Odin is killed by the great wolf Fenrir during Ragnarok (the Norse apocalypse and subsequent recreation).

Lessons from the Myths of Odin

One key difference between most current, monotheistic religious systems and the polytheistic ones of old, is the flawed nature of the latter’s gods. The Norse gods weren’t 100% “good” like the Christian Jesus or Islamic Allah. They more or less had certain desirable characteristics, but in many ways mirrored the humans who worshiped them in their faults and oddities. Odin was no exception.

He is perhaps the most complex god in all of mythology. He’s the Allfather, but also a bit of a wandering, magical shaman. In fact, J.R.R. Tolkien imagined the now-revered Gandalf as being an “Odinic wanderer” (among many other Norse influences in The Lord of the Rings). So when you picture Odin, imagine many of Gandalf’s qualities: wise, discerning, inspiring, fierce; but also quite mysterious and prone to doing things not easily explained.

Odin, like many other chieftain gods, displays characteristics that Viking culture deemed most important and worthy of emulation. Let’s take a look at those traits, the myths behind them, and what modern men can learn from the Viking Allfather.

The Relentless Pursuit of Wisdom

Odin is not an omniscient god; in fact, his chief characteristic is that he’s always seeking wisdom, even at great personal cost, as we’ll next see.

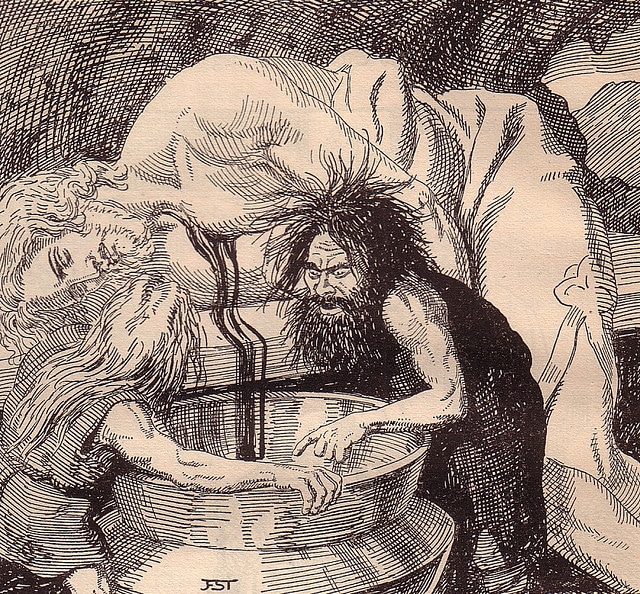

The most famous of Odin’s myths is how he lost his eye in seeking greater knowledge and discernment. The story goes that Odin visited a certain well — the Well of Urd — because he knew its waters contained wisdom. When Odin arrived, he asked Mimir, the shadowy, wise being who guarded the well’s depths, for a drink. Mimir knew the tremendous value of such a gift, however. Instead of giving a drink from the waters straightaway, he first required Odin to sacrifice an eye. Whether given easily or after an agonizing internal debate we don’t know, but Odin gored out an eye, and in return Mimir allowed him to quench his deep thirst. Odin lived the rest of his life with a single eye, but much wisdom.

One interpretation of this myth notes that Odin exchanges worldly vision (his eye) for internal vision (wisdom). While he didn’t give up his worldly sight entirely, he realized that in some cases, wisdom and discernment propel us further towards our goals than what’s on the surface. I rather appreciate this insight, and it correlates well with what Brett wrote about situational awareness a couple weeks ago (I highly recommend you read that article). Visual observation is certainly important in being aware and present, but what’s more important is orienting yourself to what you’re seeing, which can’t be done without the help of knowledge, foresight, and wisdom.

Another famed tale that communicates Odin’s relentless pursuit of knowledge is his discovery of the runes. In our modern understanding, runes are simply ancient forms of writing, but in the Viking age, they were far more than that, and held the secrets to wisdom and the very meaning of life. Let’s take a quick look at the tale:

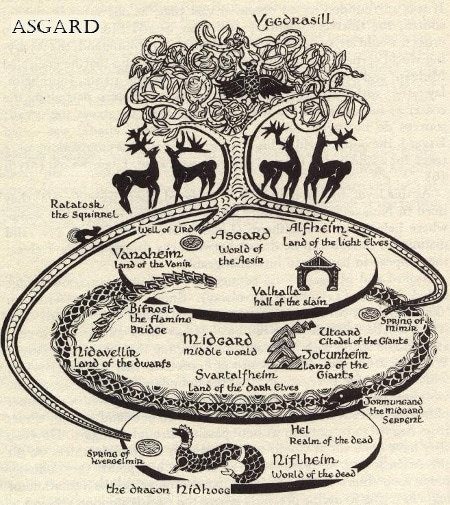

At the center of the Norse universe is the great tree called Yggdrasil (pronounced ig-druh-sill), which grows from the fathomless depths of the Well of Urd — the same well mentioned above. (Asgard, the gods’ fortress, is held within the upper branches of this great tree; it’s a biggen.) In a complicated bit of magic, three powerful and shrewd maidens called Norns carve runes into the tree’s trunk, which dictate the destiny of all the Norse worlds (there are nine worlds — most of them invisible to the human eye — in which different creatures reside; Midgard is the realm of the humans while Asgard, as just noted above, is the gods’ dwelling place). As you can imagine, understanding the runes would be quite desirable. From Asgard, Odin could see the Norns’ activity, but couldn’t discern the mysterious carvings. He envied this knowledge mightily, and decided to take on the task of finding the runes’ meaning.

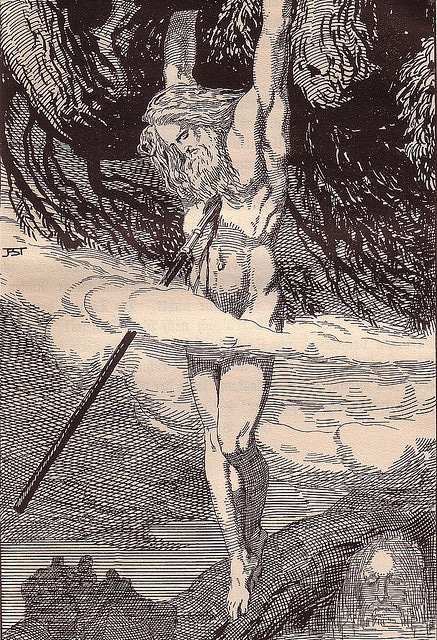

Knowing the runes only revealed themselves to those who were worthy, Odin hanged himself on the tree, pierced himself with a spear, and denied any sustenance or help from other gods. Odin peered upon the runes with an intense focus, and after teetering on the balance beam between life and death for nine days and nine nights — and perhaps even dying a little bit — Odin beheld their secrets. In spite of his pain and exhaustion, he then let out a great, beastly yell. After this, he became the great god he is known as, and wielded a number of magical powers.

In one source for this story, the Havamal, Odin says he was “given to Odin, myself to myself.” He sacrificed himself, for the sake of himself. Part of him had to die so another part could gain wisdom and understanding. It’s analogous to our more modern concept that the child is father to the man. In order to progress, small parts of us need to die every now and then to allow new shoots of wisdom to grow in their place.

The lesson from both of these tales is that gaining wisdom often comes with sacrifice. In our modern age, it seems people have come to believe that if something is hard, or sacrificial, it’s not worth doing. Odin, and his Viking followers, believed in just the opposite. If something is worth having, it absolutely requires sacrifice, and it’s always worth it, no matter how great the cost.

When it comes to wisdom, hopefully you don’t have to lose an eye, but certainly you should be willing to place time, energy, attention, and even money on the altar of your goal. Read difficult and dense books, seek challenging experiences that will push you outside your comfort zone, swallow your pride — perhaps the hardest sacrifice of all — and put yourself out there to find a mentor. Consider the sacrifices to be investments in your wisdom in the long run. It will be well worth it.

Poetry, the Gift of the Gods

Odin often spoke in poems, and was credited with giving poetry to humanity. This happened when he stole and consumed the Mead of Poetry, which unsurprisingly required a great deal of effort and sacrifice. Beyond just poetry as we think of it today, this mead was truly a source of knowledge and inspiration — it even came to be nicknamed “the stirrer of inspiration.” Drinking the mead not only gave knowledge and words to the mind, but the ability to inspire and persuade and arrange those words in meaningful ways.

The story is fairly lengthy, so I can’t give all the backstory, but you’ll get the gist of it:

In the Norse pantheon, there exists two groups of gods, the Aesir and the Vanir. The Aesir were the primary gods — Odin, Thor, Baldur, etc. The Vanir, on the other hand, were secondary gods whom we don’t have many myths about. Usually, the two groups got along, but not always. During one particular skirmish, they sealed a truce by spitting into a vat. Their spit then formed a being named Kvasir, who became yet another eminently wise creature who wandered the earth giving counsel. He not only possessed wisdom, but dispensed advice freely to those who asked.

Once upon a time Kvasir was invited to the home of two dwarves, Fjalar and Galar. When he arrived, the dwarves killed him and made a mead with his blood. This elixir contained within it Kvasir’s ability to provide wisdom, as well as inspiration. Anyone who drank it would be conferred these gifts.

Eventually, the dwarves got themselves into further trouble, and were forced to give the mead to a giant named Suttung, who hid it beneath a mountain. Odin knew the mead’s general movements, but couldn’t figure out access to the mountain. Seeing as how Odin desired wisdom and knowledge above all else, he unsurprisingly set his sights on doing whatever it took to find and drink the mead.

Odin’s first step was to go to the farm of Baugi, who was Suttung’s brother. He disguised himself as a farmhand, and dispatched the nine servants who were already there (in a clever bit of trickery he got them to all kill each other). Odin approached Baugi and offered to do the work of those nine men, and in return he wanted a drink from the mead. Baugi had no control over the elixir, but he promised to help Odin acquire it should he indeed be able to complete the work.

Odin did so, and he and Baugi trotted off to meet Suttung, who angrily denied them access to the mead. So, Odin and Baugi attempted to venture into the heart of the mountain themselves. After Baugi drilled a hole into the rock, Odin shapeshifted into a snake and crawled through into an inner chamber. Once inside, he shapeshifted once again into a young man and was greeted by a fair maiden-guardian named Gunnlod. As the guardian, she had to grant him permission, and they struck a deal in which Odin would get three sips after sleeping with Gunnlod three nights. Odin obliged, consumed three whole vats (rather than three sips), and flew off to Asgard in the shape of an eagle, where he then regurgitated some of the mead so he could dispense it to others at will.

Odin previously had knowledge and insight, but now added to that the gift of dispensing it in meaningful and motivating forms.

It’s a wonderful thing to have vision and insight, but if you can’t share it others, and convince them to take action, you’re powerless to affect the world. The potency of wisdom’s power is predicated on cultivating charisma and mastering rhetoric. Think of a man like Winston Churchill; he had a vision of where his beloved England needed to go to win the war, but his efficacy as a leader came down to his ability to change and inspire his countrymen’s hearts through his radio broadcasts and Parliamentary speeches. Pure wisdom is like electricity, and rhetoric the conduit which channels that current into effective power.

Conclusion: Odin the Breath of Life

While Odin is sometimes seen as a war god, that title belongs to Tyr in Norse mythology. Odin doesn’t often take part in battles himself, and we don’t have many war myths about him. He’s more about providing the vim and vigor warriors need to vanquish their foes. One writer from the year 1080 writes that Odin “imparts to man strength against his enemies.”

There’s an old Norse poem from The Poetic Edda that identifies Odin as “ond” — the breath of life. He provided the first humans in Norse mythology — Ask and Embla — with their animating force. It’s through his magical powers and bestowing of spirit that humanity strives to better itself, to flourish, and to rid stagnation from its existence.

While the comparison isn’t perfect, it seems like Odin to the Norsemen is what thumos was to the Greeks. Wisdom, passion, and inspiration are his domain, and as we’ve seen, he sacrificed much to attain those traits.

And Odin expected humans to do the same. The Norse culture, like many ancient ones, wasn’t a democracy, but a meritocracy. You had to work for your blessings from Odin; they weren’t just handed down freely. In tale after tale, men had to literally and metaphorically bleed themselves in order to attain their aims and transform into warriors — the only type of man who had a chance at accompanying the Allfather to Valhalla.

As we’ve seen over and over on the Art of Manliness, characteristics like passion and vigor are not necessarily inherent within us. It’s through action and work that we build up these properties and form the foundations of who we are. Follow the example of Odin and relentlessly pursue wisdom, even sacrificing time, energy, money, etc. to obtain it. Study not just for the sake of knowledge, but to be able to convey that knowledge to others; come to learn the intersection of information and expression. Let the great, bearded, one-eyed Chieftain serve as one of your invisible counselors; he’ll advise you in perhaps mysterious ways, but also always towards fierce inspiration and wisdom.

Read the Series:

______________

Sources and Further Reading

Gods and Myths of Northern Europe by H.R. Ellis Davidson. This textbook from 1965 is a surprisingly readable guide to not only Norse myths, but their context and symbolism within the Viking culture.

The Age of the Vikings by Anders Winroth. This is a history of the Viking people, rather than a specific look at Norse mythology. It helps set the stage, however, and does well in giving an honest account of their culture.

The Poetic Edda (Hollander translation). A collection of anonymous mythical poetry and verse from the 1300s that serves as an origin text for many Norse myths.

The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. A textbook-like work from the Icelandic historian which compiles Norse myths. This, along with The Poetic Edda, offer the majority of source material for Norse mythology.

Nordic Gods and Heroes by Padraic Colum. This is a collection of reimagined and rewritten Norse myths. They’re in a language that captures the beauty and inspirational nature of the tales rather than a rote translation of ancient words.

Norse Mythology for Smart People. An online treasure trove of articles and information about the mythological Norse universe.